|

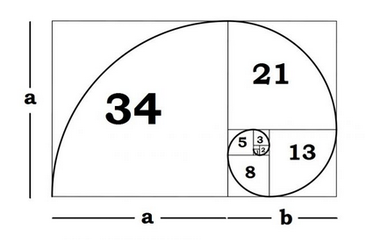

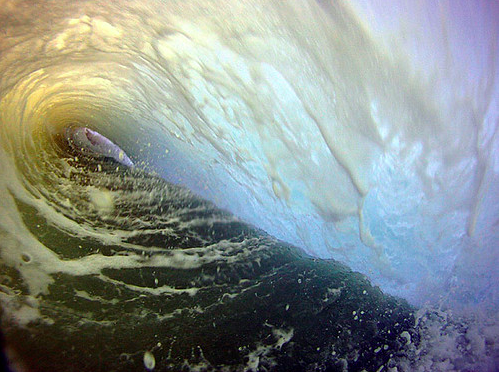

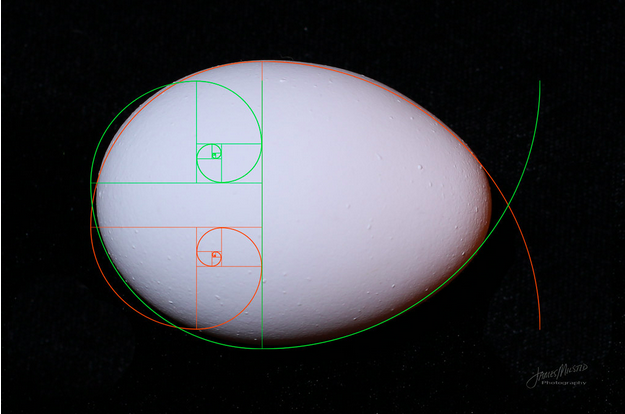

"The richness I achieve comes from nature, the source of my inspiration." – Claude Monet For centuries, people have been designing gardens for residences and public spaces. As a result, the field of garden design offers us a wealth of styles and information to turn to, keeping gardeners busy learning how to create the perfect outdoor paradise. Gardens give us pleasure, they calm our senses and they help us to slow down and relax. Gardens provide beauty and inspiration and can help heal the sick. Gardens provide sanctuary, solace and a peaceful place to return to our connection to the natural world. It is this final perspective, helping our clients find their connection to nature, that we embrace in our designs. In order to foster those connections, we are intimately focused on how nature works from both an ecological and an artistic perspective. The beauty of nature can be felt and it can also be interpreted. Nature in and of itself can seem chaotic, but within the seeming-chaos lies a tremendous amount of mathematical order. Studying natural systems has allowed designers over the ages to discover certain mathematically-based patterns. Once the order within the chaos is understood, a whole world of design potential opens up. Playing with the idea that there is order within the chaos of a garden gives the gardens we design a sense of harmony. Within the spectrum between wild and tame lies the sweet spot in our designs. Mariposa’s gardens and our designs gain strength from observing the patterns of nature and then replicating those patterns in the garden during design and construction. Some of the patterns we use in our designs include symmetries, fractals and spirals. Repeating these patterns when laying out hardscapes or placing plants is one of the ways we replicate natural systems in our designs. Symmetries: There are several kinds of symmetry. In nature, bilateral and radial symmetry are common. Bilateral symmetry means an object has a left side and a right side that are mirror images of each other - most animals and insects demonstrate bilateral symmetry. Radial symmetry, like the form of a daisy, is common in flowers even when the rest of the plant exhibits little or no symmetry. Here’s an example of how we used radial symmetry in the design of a stone wall: Fractals: A fractal, according to Merriam Webster, is “any of various extremely irregular curves or shapes for which any suitably chosen part is similar in shape to a given larger or smaller part when magnified or reduced to the same size.” If you look closely at the picture of romanesco broccoli below, you’ll notice that the same shapes and curves are repeated over and over in smaller and smaller sizes. Fractals occur in many places in nature. They are essentially repeating patterns that course through an organism. For example, fern branching patterns start with the leaflet pattern as it goes down the stem. Then, the leaflet itself matches the pattern of the branching form. Trees also repeat their branching pattern from the trunk out to the newest branches. The branches grow out from the trunk and then fan out in a similar pattern throughout the tree. Each tree has its own sort of fractal pattern. One of the ways we use fractals in our designs is by repeating patterns within our stonework or in our patios. We also use repeats in our planting layouts. For example, we may repeat the same groupings of plants throughout a bed. Spirals: A spiral is defined by Merriam Webster as “the path of a point in a plane moving around a central point while continuously receding from or approaching it.” Spirals are all around us: the center of a sunflower is a complex spiral, as are the plates of a pineapple. Vine tendrils spiral around the objects they cling to, helping the vine to climb. The DNA double-helix is a spiral; our Milky Way galaxy is a spiral; hurricanes, water going down a drain, nautilus shells, snail shells - even your fingerprints - all spirals.  The Golden Mean The Golden Mean This post by blogger Sam Woolfe offers a fascinating look at why spirals are so common in nature, and why they have been seen as a mystical and sacred form by so many civilizations over the centuries. Mr. Woolfe’s blog offers an introduction to “Fibonacci spirals,” which are logarithmic spirals based on the Fibonacci Sequence, and which adhere very closely to “the Golden Mean.” The Golden Mean, also known as the Golden Ratio, is a mathematical concept that is expressed in nature’s patterns. It is another way we use the mathematical order found in nature to complement how we lay out our garden designs. Otherwise known as the Golden Ratio a+b is to a as a is to b. This mathematical ratio is found in the way that ferns unfurl, roses bloom, seashells form, petals are arranged on a flower, pineapples grow and on and on. The wave in the picture below demonstrates the Golden Mean proportions. Examples of the Golden Mean are endless in nature, and mathematicians have given us the tools to understand natural proportions so that we may recreate them in our work. The ancients used this ratio when building some of the great works of architecture. Artists often use the ratio to create pleasing proportions in their art. In the garden, we can lay out hardscapes and other elements within the garden using the Golden Mean to great effect. At Mariposa, we design our lines in the landscape, the shape of planting beds, the proportion of planted area to hardscapes to this mathematical this proportion. Our “Seed” sculptures and fountains are designed using the Golden Ratio of 1:1.61. Our “Seeds” are often seen as “eggs” or “beehives” or various other forms seen in nature that follow this same proportion. Using the Golden Mean in design is a way of bringing order to the chaos. The Golden Mean is closely associated with the Fibonacci Sequence. This sequence of numbers is useful when thinking of how to pattern stonework and other hardscapes. It can also be useful in plant layout. For example, when we want to add an element to a stone seed sculpture, we use the Fibonacci Sequence of 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89 to determine where to add the decorative element. In the sculpture shown below we created the pattern of light and dark layers using the Fibonacci Sequence. Using rhythms and repeats in plant layout is a good way to engage the garden visitor. Laying out repeats with the sequence in mind is a way of creating order within the chaos that may not be consciously perceived, but is felt. It is the element that makes the garden sing. We use the sequence to determine how much space to leave between plantings too. If we have five very colorful red flowers that we want to incorporate into a garden area, we lay them out with the amount of space between each plant coordinating to the Fibonacci Sequence: two at 1 foot apart, the next at 2 feet apart, the next 3 feet apart, the next 5 feet apart, and so on. This spacing provides a rhythm that creates a feeling of order, even though it may look random. Because this mathematical sequence is seen all over nature, it is familiar, even when we are not consciously aware of it.

Next time you visit a public garden or landscaped parkland, whether the garden is formal or informal, spend some time observing how the design uses rhythm and pattern to bring order and beauty into the space. Or when you take a walk in a forest or on the beach and look for symmetry, fractals, and spirals. We think you’ll be amazed at what you see. If you try this exercise, please share what you find in the comments!

6 Comments

|

Categories

All

AuthorAndrea Hurd, founder of Mariposa Gardening & Design. Archives

June 2024

|

|

License #1038752

|

Mariposa Gardening & Design

Address: 2323 Broadway Oakland, CA 94612 Mailing Address: PO Box 24072 Oakland, CA 94623 [email protected] |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed